Hong In-sook is an artist whose works straddle the line bet

ween text and im

age. In a warm and humorous way, she offers a modern interpretation of the

munjado genre, Korean folk paintings of pictorial ideographs.

Hong In-sook in her studio. Since her first solo exhibition at the Kyungin Museum of Fine Art in 2000, she has displayed high originality in her art. The artist writes down ideas whenever they occur to her, reflects on them for some time, and then visualizes them in her work.

Hong In-sook’s solo exhibition Re-rising Moon, Worin cheongangjigok was held last May at the Moryham Exhibition Center in Hoehyeon-dong, Seoul. Worin cheongangjigok (Songs of the Moon’s Reflection on a Thousand Rivers) is a Buddhist hymn book written by Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450), fourth monarch of the Joseon Dynasty, as a tribute to his late wife Queen Soheon.

In the works that were on display, Hong delves into the emotions of losing a loved one, using characters and images representing the moon, light, and love. She transformed characters into pictures and pictures into characters, blurring the line between text and image. In her reinterpretation of traditional pictorial ideographs, where text and image are perceived as one, Hong explores the enduring values in our lives.

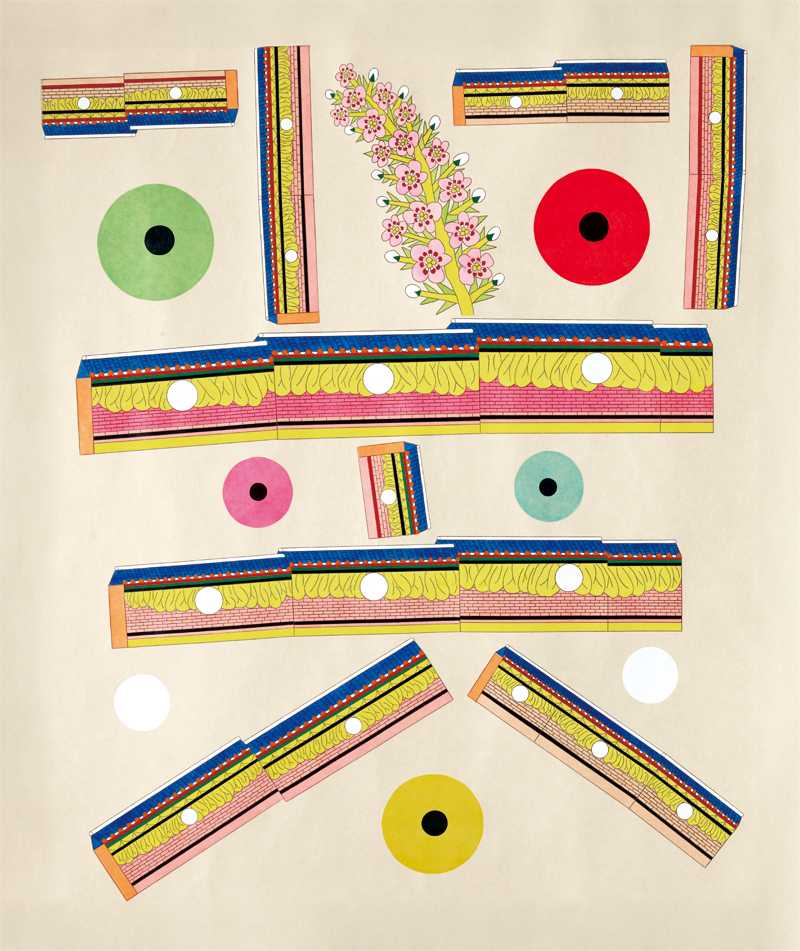

Single-Letter Landscape: Flower (꽃). 2024. Print on paper, drawing, and color on hanji.

140 × 118 cm.

© Hong In-sook

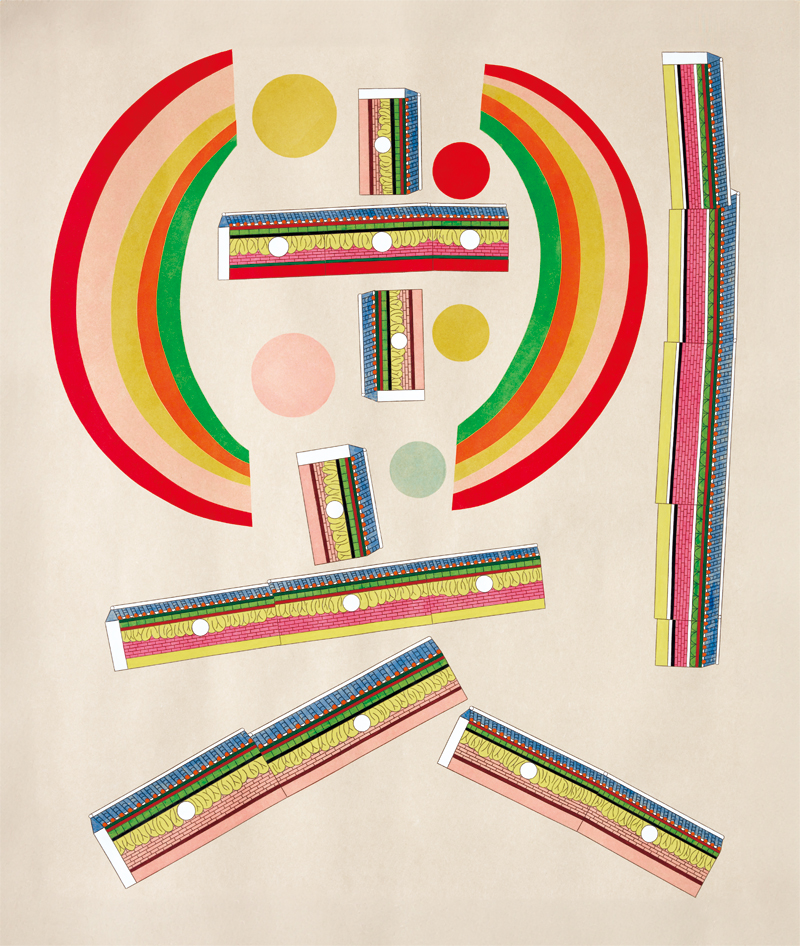

Single-Letter Landscape: Light (빛). 2024. Print on paper, drawing, and color on hanji.

140 × 118 cm.

© Hong In-sook

The artist asks the question “What are the words that give people strength?” in the form of traditional pictorial ideographs. These works were exhibited in Re-rising Moon, Worin cheongangjigok, held at the Moryham Exhibition Center in May this year.

CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

Munjado is a type of Korean folk painting, a pictorial rendering of classical Chinese characters with stories related to their meaning incorporated into the strokes. These paintings generally fall into two categories: those emphasizing the virtues of Confucianism, the official state philosophy of the Joseon Dynasty, such as filial piety, loyalty, and trust; and those expressing wishes for blessings, such as wealth, longevity, happiness, and good fortune.

“My work differs from traditional munjado,” Hong explains. “As the elements [in my paintings] come from my childhood experiences, they are far from societal values or wishes for good fortune.”

The artist describes her work as “single-letter landscapes,” where monosyllabic Korean words such as dal (moon), jib (home), kkot (flower), bab (meal), and ppang (bread), are visualized in Hangeul in a way that blends past memories with visions of the future.

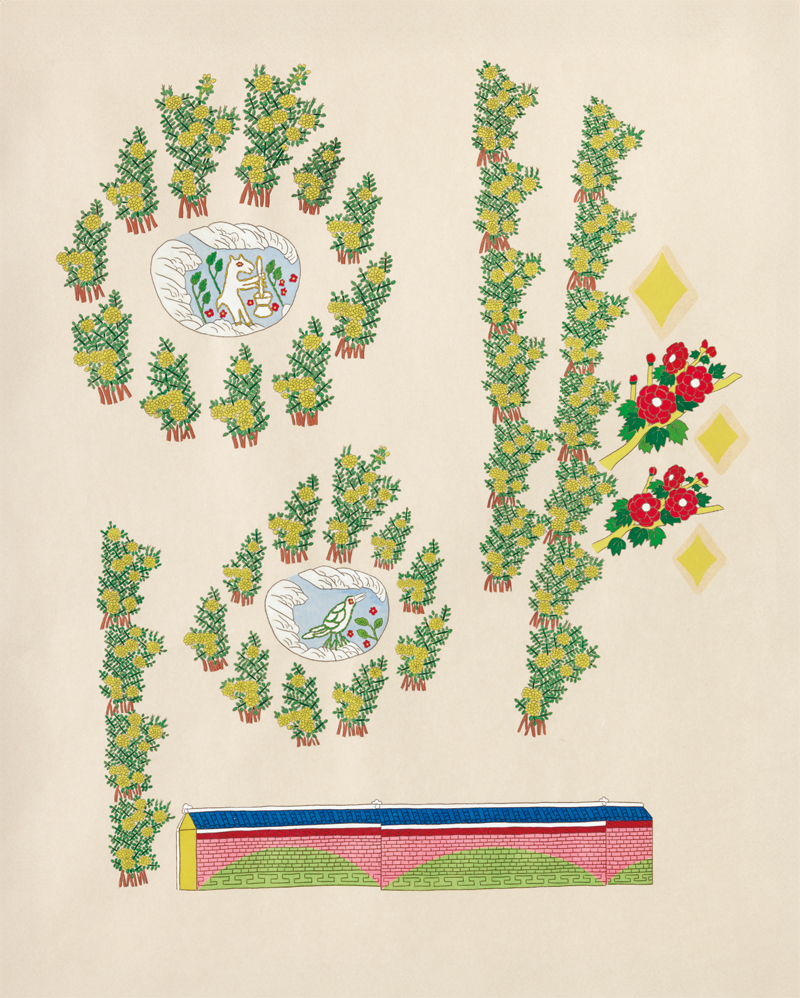

Single-Letter Landscape: Well (안). 2020. Print on paper, drawing, and color on hanji.

110 × 90 cm.

© Hong In-sook

Single-Letter Landscape: Being (녕). 2020. Print on with paper, drawing, and color on hanji.

110 × 90 cm.

© Hong In-sook

Hong In-sook’s exhibition Ann, yeong, held at Kyobo Art Space in 2020, reflected on the significance and preciousness of daily wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time of universal suffering. The artist presented the two characters an (안) and nyeong (녕), constituting the Korean word meaning “well-being,” which also serves as an everyday greeting.

PRINTMAKING TECHNIQUES

Hong’s work features childlike pencil sketches, comic book-style girls, and enclosure walls formed from the strokes of the characters. Her style is playful and kitsch, while also exhibiting aspects of simple traditional painting. However, the elements that make up the scenery — trees, flowers, birds, people, etc. — have a certain craft-like quality to them. This is because they are not drawn by hand.

“I majored in Western painting in college and printmaking in graduate school,” says Hong. “I thought printmaking suited me, but something was missing. I was feeling limited by Western material when I found the answer in hanji [Korean mulberry paper] and delicate Eastern painting techniques.”

The bright, lucid colors in her work are the result of applying intricate printmaking methods. Hong begins by drawing a sketch on standard paper and then creates a carbon copy on hanji. Next, plates are cut out of paper for each color, which are then painted and pushed down repeatedly onto the canvas with a press. The position of the plates is changed each time in order to achieve the desired color effect.

“It might seem as simple as stamping, but each printing procedure requires intense concentration. While it could be done easily on a computer by copying and pasting in Photoshop, doing it all by hand is completely different. The slight misalignment and imperfections that occur are natural and give life to the artwork,” Hong explains.

Hong’s techniques produce colors that have a different feeling to those of conventional brush paintings. Although her work is technically printmaking, she doesn’t create multiple editions, because each piece, made with numerous color plates and pressing procedures, is one of a kind.

“People who have seen me at work say the process is so silly that it almost seems smart. It’s neither as quick as drawing nor as sleek as computer work. It’s a method that I invented while trying to find what suited me best.”

Hong uses rollers of various sizes for printmaking. Through her long exploration of the genre and control of the physical pressure applied, she has created a sensitive and concise style.

LANDSCAPE OF CHARACTERS

Born in 1973 in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi Province, Hong was the eldest of three children. Until starting elementary school, she grew up in the countryside where there were no other children to play with. Her only playmates were trees, flowers, grass, and books.

“While sorting through my father’s possessions after he passed away, I found a well-worn book with my childhood scribbles tucked between the leaves. The big-eyed girl that I often draw is inspired by those early sketches,” she says.

Hong experienced a profound loss at the sudden death of her father, just after she became a full-time artist. Her father had given her a strong sense of refuge and protection, and after losing him she produced works in quick succession, as if searching for a lost love.

A fusion of printmaking and painting, Hong’s work appears to be somewhere between Eastern and Western painting. At the same time, it resembles a form of illustration or graphic design. With its hybrid form and refreshingly simple style, her approach has garnered attention since her early solo exhibitions, such as Peony and True Love, as well as Always a Little Late, held in 2003 and 2006, respectively.

The artist’s home-cum-studio faces the walls of Suwon Hwaseong, a Joseon Dynasty fortress and UNESCO World Heritage site. The house is a renovated old Western-style building and doubles as a gallery and open space for students learning printmaking.

“I enjoy working alone, but I also cherish the time spent communicating with like-minded people,” says Hong. Her experiences of loss and a solitary childhood in the old fortress town of Suwon continue to influence her work as her landscapes of characters evolve.

Realize. 2011. Color on cotton. 116 × 90 cm.

© Hong In-sook

Hong incorporates into her work elements of traditional Korean painting, such as blank spaces, poetic text, and seals. She also conveys complex messages by combining Chinese ideograms, facilitating the literary and narrative expr