Yecheon County in North Gyeongsang Province is home to one of ten sanctuaries to which people retreated in turbulent times during the Joseon Dynasty. The area has a deep community spirit and an inviting natural environment that reflects Korea’s traditional beauty.

ⓒ KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

As in most countries, Korea’s first settlements sprouted along rivers or in coastal areas, forming hubs of commerce and transportation. Yecheon County, a remote mountainous area in North Gyeongsang Province, is where South Korea’s longest waterway, the Nakdong River, meets two other streams, Naeseongcheon and Geumcheon. The area naturally attracted early inhabitants who relied on riverboats and trade.

The Hoeryongpo Observatory, an elevated traditional pavilion near the top of 240-meter-high Mt. Biryong, provides an expansive view of one of the county’s best-known sites: the tear-shaped village of Hoeryongpo (lit. a place by the waterside where a dragon turns). The village takes both its name and its moniker — “an island within the mainland” — from the shape of the Naeseong Stream that nearly encircles it.

The confluence of the Nakdong River and its two tributaries occurs about two kilometers from the observatory. Before the advent of railroads and motor vehicles, boats made pickups and deliveries at this intersection more than 30 times a day as travelers shuffled in and out. A flood in 1934 swept away everything except for Samgang Tavern and a 500-year-old spindle tree standing next to it. The tavern still exists, but an establishment next door continues its legacy by serving baechujeon (cabbage fritters) and makgeolli (traditional rice-based alcohol) that once satiated the hunger of wayfarers centuries ago.

As postwar South Korea urbanized, its rural counties emptied out, with Yecheon losing more than half of its population. Today, thanks to tourist guidebooks, TV series, and social media posts, Hoeryongpo Village and its observatory are popular destinations. But my recent trip to Yecheon highlighted a lesser-known aspect of Korean history and culture that can’t be found in urban centers.

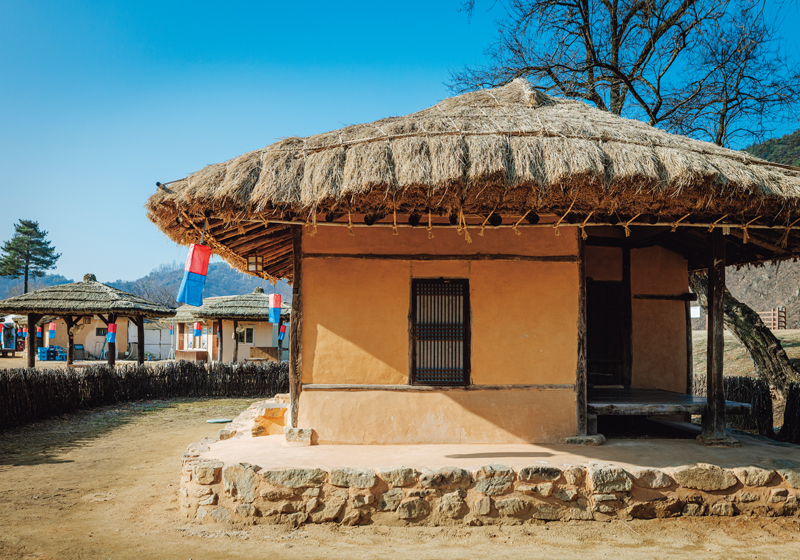

Geumdangsil Village. Traditional houses from the Joseon Dynasty still retain their original appearance, and Bronze Age dolmens dot the village. Other attractions include a labyrinthine stone wall and a pine forest, designated as Natural Monument No. 469.

© Yecheon County

IDYLLIC HAVENS

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), Sipseungjiji (Ten Sanctuary Places) referred to the ten places that best embodied the traditional Korean concept of the ideal location to live. Most were tucked away in the recesses of the interior, well off the beaten track. With fertile soil and accessible distribution networks, they afforded residents a peaceful and prosperous life.

Geumdangsil Village, a 40-minute drive from Samgang Tavern, was one of the Sipseungjiji. Bronze Age dolmens around the village testify to the area’s ancient legacy. Today, dozens of hanok, or traditional Korean houses, stand surrounded by a seven-kilometer-long labyrinthine stone wall, exuding a quaint charm.

Taking a leisurely stroll through Geumdangsil, it is easy to understand why it became a preferred refuge. The village is surrounded by vast rice fields, with the majestic Sobaek Mountains to the north offer a towering backdrop. Geumdangsil was far enough from Joseon Dynasty transportation routes to be of little value to invaders, but not so far removed that it was inaccessible to suppliers.

Some 900 pine trees spanning 800 meters buttress the village’s northwestern boundary. They were planted centuries ago by locals to guard against the frequent flooding of nearby Geumcheon. The forest is now protected as a natural monument for its scenic beauty and historical significance. In the spring, cherry blossoms transform the seven-kilometer road to Yongmun Temple into a billowy funnel of pink.

Samgang Tavern is designated as Folklore Cultural Heritage No. 134 of North Gyeongsang Province. Centuries ago, it provided meals and lodging to peddlers and boatmen.

ⓒ Shin Jung-sik

A child trying its hand at beona dolligi, or saucer spinning, which features in traditional Korean folk performances, at the popular Samgang Tavern Ferry Festival.

ⓒ Yecheon County

SCHOLARLY HERITAGE

Yecheon is essential to the history of Korean encyclopedias. Its noble families used their privileges and prosperity to pass on knowledge to others, rather than keeping it for themselves.

When Gwon Mun-hae (1534–1591), a Joseon Dynasty civil court official, returned home to retire here, he sought a place to nourish his mind, body, and spirit. He found it in the valley now famous for its cherry blossom road: a vertical rock where he could perch and immerse himself in the atmosphere of the pine forest and the stream. The mist rising off the water in spring would have added a mysterious aura, evoking a divine paradise where immortals were believed to reside.

In 1582, Gwon built a thatched-roof house on his idyllic spot. After his death, it was burned down during the Japanese invasions between 1592 and 1598, then reconstructed in 1612, only to be destroyed again in the winter of 1636 during the Qing invasion. The pavilion that currently stands at the site was built in 1870 and named Choganjeong.

Gwon used his oasis to compile Encyclopedia of Korea, Arranged by the Rhymes of the Entries (Daedong unbu gunok), regarded as Korea’s first encyclopedia. It covers a range of topics from ancient times to the 15th century, including Korean history, geography, people, animals, plants, and folktales.

Among the traditional units used to count old books, “gwon” corresponds to a chapter that divides a piece of writing based on distinct topics, while “chaek” refers to an individual book that is part of a larger collection. Gwon’s reference work is a compilation of 20 chapters (gwon) divided into 20 books (chaek).

At the oasis Gwon Mun-hae d, his son Gwon Byeol (1589–1671) wrote Miscellaneous Records of Korea (Haedong jamnok), an encyclopedia detailing the stories of government officials that appeared in Daedong unbu gunok. Two mid-19th century scholars from Yecheon also d important works. Bae Sang-hyeon (1814–1884) compiled Encyclopedia of Laws and Regulations of Korea (Dongguk sipji), which covers a wide range of topics such as criminal law, rice farming, and geography, while Park Ju-jong (1813–1887) compiled Encyclopedia of Traditional Korean Culture (Dongguk tongji), ing Joseon’s traditional culture and history in 14 subjects.

Choganjeong, an archetypal Joseon pavilion, stands at the bend of a creek in peaceful harmony with the surrounding nature.

© Yecheon County

GIFTS THAT KEEP ON GIVING

Yecheon forebears’ brilliant wisdom for the well-being and solidarity of the inhabitants is evident: two trees here are official landowners. One is a massive pine tree whose branches stretch 23 meters from east to west and 30 meters from north to south. The other, equivalent in size, is a hackberry tree called Hwangmokgeun.

The nearly 650-year-old pine tree in Cheonhyang Village was the first in the country to own a piece of land. A childless man named Lee Su-mok, after much thought, decided to leave his 6,600-square-meter property to the pine tree, which he named Seoksongryeong, or “magical pine tree.” In 1927, the tree entered official land ownership records.

Why didn’t Lee leave the land to a relative or close neighbor? In hindsight, it is easy to understand his rationale. Individuals and organizations lease the tree-owned land, and the profits are used to fund scholarships for local students. Bequeathing the land to a specific individual could have caused discord in the village, but its collective management ensured that the money collected in its name would be used for the community’s benefit. Today, almost 100 years later, Seoksongryeong is still accorded the respect of a human owner, and the villagers remain devoted to its care. They protect the tree from inclement weather, and a lightning rod has been placed to prevent it from being struck. Scores of students have been able to graduate thanks to the Seoksongryeong Scholarships, and many more continue to benefit from them.

Hwangmokgeun stands in Geumwon Village, a 30-minute drive from Seoksongryeong. The hackberry tree, which gets its name from the yellow flowers blooming around it in May, owns 13,620 square meters of land, more than double that owned by Seoksongryeong. In this case, the land was initially the joint property of the community, and its ownership was transferred to Hwangmokgeun in 1939. The land here also generates rental income, which is used to award annual scholarships of around 300,000 won to the village’s middle schoolers. Geumwon Village has records of community donations dating back more than 100 years. Before meals, each household put aside a spoon of uncooked rice that was to be used to help less fortunate families. Among the records are the minutes of the 1903 Geumwon Community Association Meeting and the 1925 Savings and Relief Association Executive Meeting.

Seoksongryeong, a massive pine tree in Cheonhyang, is considered the guardian of the village’s well-being and peace. It has an unusual shape with elongated branches three times as long as its height, which are propped up with stone and metal pillars.

© Kwon Ki-bong

"WORD TOMB"

The wisdom of promoting community solidarity and peace by showing consideration for others culminates in southern Yecheon’s “word tomb.” What appears at first glance to be an ordinary hill is an artificial structure, built with rocks and soil, that resembles a huge tomb. Locals of yore decided to build it in order to “bury” words as a measure against conflicts in the village. After all, words are often the seeds from which conflict grows.

What made Geumdangsil Village one of the Sipseungjiji and how does it continue to thrive? With its tranquil atmosphere, spacious fields, and an functioning distribution channels, Geumdangsil remains an ideal location. Instead of escaping the wars and political upheavals of the Joseon Dynasty, villagers today can escape the incessant stress and unforgiving competition of the cities.

But the natural surroundings and geographical advantages are not the only factors. The atmosphere of understanding and consideration for others is just as essential. Traveling around Yecheon, this becomes apparent all around you.

Residents of yore built a “word tomb” to bury words of conflict and pacify strife among villagers. Phrases engraved on the stone advise residents to be mindful about what they say.

© Shin Jung-sik

ⓒ KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

ⓒ KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

ⓒ KOREA TOURISM ORGANIZATION

ⓒ YecheonCountry